Nature versus nurture has been an argument for almost as long as the field of psychology has existed. Simply put, this argument debates how our personality is developed. Are we born with our personalities, or do our experiences shape our personality? This debate can also be interestingly translated to fear. Are we born with our fears, or are our fears shaped by our experiences? Modern neuroscience has figured out that while we have an innate fear of a few general things, most specific fears are learned.

The Amygdala

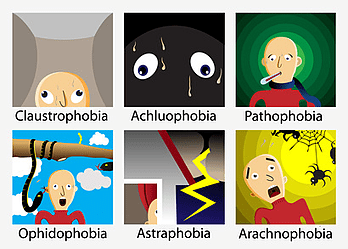

Fear all starts with the amygdala: an almond-shaped part of the brain that basically serves as our fear processing center. The amygdala is equipped with what neuroscientists refer to as evolutionary preparedness (an affinity for quickly acquiring certain fears useful to our ancestors’ survival). This explains why humans from all cultures more easily learn to fear snakes, spiders, and heights than electric outlets or cars, although the latter objectively represent far greater threats in everyday life today.

But evolutionary preparedness is only the starting point. Think of it as though a state-of-the-art burglar alarm had been installed in your house: the wiring is in place, but the program of what constitutes a real threat has yet to be added. This program is known as fear conditioning.

Fear Conditioning

The amygdala, when detecting a dangerous situation, communicates with the hippocampus (the center of our memory) and the prefrontal cortex (the area of our brain responsible for logical thinking) to solidify fear memories. These are not just mental snapshots but complex neural networks that include sensory information, bodily responses, and emotional associations. Every time we find ourselves in a similar situation, these networks are activated and thus potentially strengthened, which could explain why fears can worsen over time.

Curiously, the brain’s neuroplasticity (capacity for change and connection between neuron) allows it to learn and unlearn fears throughout life. Scientists have been able to show that the strength of fear memories can be updated during a reconsolidating process, wherein memories temporarily become malleable when they are recalled. Hence, reconsolidation has revolutionary implications for the treatment of phobias shown below and other anxiety disorders.

Factors for Fear Conditioning

The environment forms our fears through various factors. Direct experience is perhaps the most obvious (a dog biting a child may produce cynophobia) but we can also learn fears through observation (watching another person injured) or through instruction (being repeatedly told that something is dangerous). Social and cultural influences explain why some fears crop up in certain societies more than in others.

Another important factor is the age at which we experience certain fears. In childhood, our brain is much more neuroplastic, and early experiences have the deepest impact on fear conditioning. During this time, the critical development of the amygdala and prefrontal cortex occurs, and traumas during this age may have a significantly long-lasting effect on responses to fear.

The process also engages vital stress hormones such as cortisol. When we are stressed, these hormones amplify memory formation, thus making us remember fear-filled experiences for many years, even decades. That may explain why traumatic events can cause such potent and long-lasting fears: our brains remember these events (and the fear associated with these events) for our whole life

Recent studies have even indicated that some of these fear memories could be passed down epigenetically via epigenetic tags. Epigenetic tags can turn genes on or off; thus, some traumatic memories in your ancestor might have created those epigenetic tags passed on to you, influencing your fear responses and further muddling the nature-nurture debate.

Understanding the neuroscience of fear is very important for the treatment of anxiety disorders and phobias by scientists. Being able to realize that fears are largely built and not purely inborn may provide more appropriate interventions aimed at neural mechanisms of fear learning and memory. This understanding offers hope that even deeply entrenched fears might be reshaped by ingenious therapeutic interventions that work with, rather than against, our brain’s natural processes.

Leave a comment