Information theory, originally developed by Claude Shannon, explains how information is transmitted and stored. From its introduction, information theory has had several notable impacts in fields like telocommunication and notably, neuroscience.

What is Information Theory?

In 1948, while working at Bell Labs, Claude Shannon published “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” introducing concepts that would revolutionize multiple fields, from telecommunications to neuroscience.

At its core, information theory provides a mathematical framework for quantifying, storing, and communicating information. It was originally developed to address practical problems in data transmission, but its principles apply to any system that processes information—including the brain.

Entropy (H) is one of the most important concepts in information theory. It is a measure of uncertainty or unpredictability in a system. Mathematically, for a random variable X with possible values {x₁, x₂, …, xₙ} and probability mass function P(X), X’s entropy is defined as:

H(X) = -∑P(xᵢ) log₂ P(xᵢ)

The probability mass function P(X) simply describes the probability distribution of a discrete random variable—it tells us how likely each possible outcome is. For example, if we’re examining whether a neuron fires in a given millisecond, P(1) might be 0.05 (5% chance of firing) and P(0) would be 0.95 (95% chance of not firing).

Higher entropy corresponds to greater uncertainty or surprise. A neuron with highly variable, unpredictable firing patterns has higher entropy than one with regular, clockwork-like firing. Higher entropy has important implications:

- More information capacity: Higher entropy neural signals can theoretically carry more information per second

- Greater “surprise value”: In information theory, surprising (low-probability) events contribute more information than expected ones

- Enhanced sensitivity to novelty: Neurons that respond with high-entropy patterns to novel stimuli effectively flag those stimuli as information-rich

Therefore, a fair coin toss has higher entropy than a biased one because the outcome is less predictable. In information-theoretic terms, entropy quantifies the average amount of information conveyed by identifying the value of a random variable.

Mutual information (I) measures how much knowing one variable reduces uncertainty about another. For two random variables X and Y, the mutual information is calculated with the following equation.

I(X;Y) = H(X) – H(X|Y)

H(X) represents the entropy of X, and H(X|Y) represents the entropy of X after knowing Y. Hence, this equation represents the reduction in uncertainty about X after observing Y. If knowing Y perfectly predicts X, then mutual information is maximized. If X and Y are completely independent, mutual information equals zero.

Other key concepts include:

- Channel capacity: The maximum rate at which information can be transmitted with arbitrarily small error probability

- Redundancy: The repetition of information to overcome noise or transmission errors

- Compression: The removal of statistical redundancy to represent information more efficiently

These principles have proven remarkably versatile, applying to everything from data compression algorithms to genetic codes—and neural information processing.

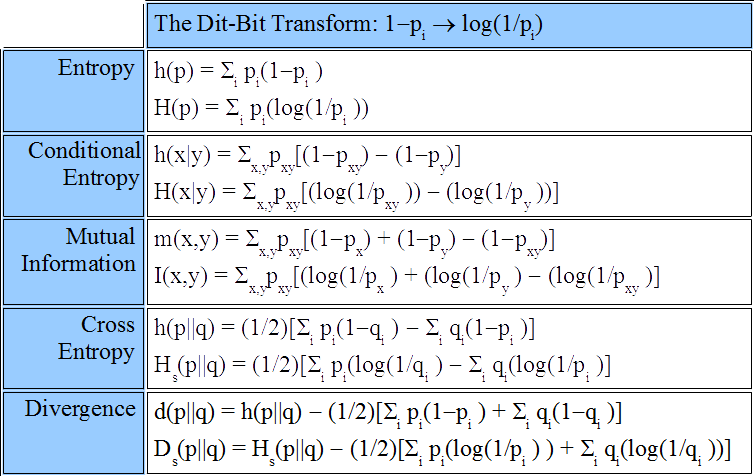

*Note that a lot of the formulas have been simplified in this explanation. All full length formulas for all types of entropies are shown below.

The Brain-An Information Processor

When we see sunsets, feel the sand in the beach, or hear a voice from across the room, our brains are processing information. In essence, the nervous system is a web of neurons, each acting as receivers and transmitters of information in the form of electrical and chemical signals. This view has led to several neuroscientists shifting their view of neuroscience from a descriptive qualitative field to a mathematical data based field.

Hence, viewing the brain with the information theory framework seen above explains several interesting brain phenomena. For example, neurons fire stronger when seeing novel stimuli – stimuli that have a higher entropy. Furthermore, neurons that recieve the same information are clumped in regions to efficiently share the information.

Sensory Systems as Information Channels

Another correlation between information theory and our nervous system are our sensory systems.

The efficient coding hypothesis, proposed by Horace Barlow in the 1960s, suggests that sensory systems have evolved to maximize information transmission given biological constraints like noise and energy limitations. This hypothesis has successfully predicted numerous sensory system properties.

For example, let’s look at vision. Typical scenes contain pixels often have similar brightness and color as their neighbors. Our visual system exploits these regularities through center-surround receptive fields that emphasize contrast rather than absolute light levels. Information theory shows this way of emphasizing constrast maximizes information transmission by reducing redundancy.

Similarly, the cochlea performs an analysis of sound, with different hair cells responding to different frequencies. This arrangement optimizes information transfer about the complex acoustic environment while working within neural bandwidth constraints.

Information theory also explains why sensory systems adapt to stimulus statistics. When we enter a dark room, our visual system adjusts to maximize information about the new, dimmer environment—sensitivity increases but absolute accuracy decreases, a tradeoff that optimizes information transmission under changing conditions.

Conclusion

As we learn more and more about the brain, the more mathematics, statistics, and computational methods are needed. Information theory is one such method. By viewing neurons as information channels and neural circuits as communication networks, we can use concepts in the field of information theory as quantitative tools to measure, model, and ultimately understand the brain.

Leave a comment